than any other country in the world*

Stop ISRAELI WAR CRIMES and GENOCIDE

|

ISRAEL MURDERED MORE CHILDREN

than any other country in the world* Stop ISRAELI WAR CRIMES and GENOCIDE Your Seeds Source...

| ||

| ||

This Chilean spring in the North was one of the driest in a decade, with rainfall bordering 30 - 40 % of the normal. So there was not the slightest ray of hope to see the blooming desert, an extraordinarily beautiful event when the desert comes alive with colorful carpets of flowers for a few weeks. And yet the temptation to make a trip to one of the most intriguing areas of Chile is difficult to resist so that it is easy to invent excuses and justify a rather foolish undertaking...

In fact as soon as I reached the coastal areas some 200 km. north of Santiago, I understood that one should take much more seriously the rule of thumb: if it rained less than 50 mm. during winter, forget about the blooming desert. This year, La Serena, a city about 500 km. north of Santiago had less than 30 mm... And the blooming desert area "officially" begins even further north.

So to somehow save the rather hopeless situation I decided to concentrate on the interior valleys of the north, namely the Huasco Valley where the main city is Vallenar and La Serena. with its Agua Negra Pass.

As I suspected that I might have to do this change of plans to visit the interior valleys instead of the coastal desert, I brought a few publications with me, which turned out to be very helpful for identifying the plants of the high Andes. For the Vallenar area, it was "The Flora of the Cordillera de Los Andes in the Area of Laguna Grande and Laguna Chica, III Region, Chile", by Mary T. Kalin Arroyo and others, published in Gayana Botanica 41 (1-2): 3-46, 1984. It was a simple list of about 300 plants with very short descriptions of the plants. I was surprised to find out that this was the first expedition since 1920' and that only three botany scientists have visited that area before, including the legendary Philippi around 1853-54. So I was going in into a black hole.

Vallenar town receives on average about 60 - 80 mm. of rainfall a year, and the surrounding desert areas even less, about 50 mm. or two inches. So when you start driving up the Huasco valley you are pleasingly surprised to find it very lush with green. Unfortunately, most of it corresponds either to foreign weeds or to plantations. And the valley is quite narrow, in the area of Vallenar it is about 800 m. wide and when you reach the middle reaches around El Transito it narrows down to maybe 200 - 300 meters. On the sides of the valley the vineyards and avocado plantations creep up the slopes generating a stark contrast with the surrounding barren mountains. It is extraordinary feat of engineering, because all the water is generally pumped up from the river level and the plants are protected on the sides and in some cases even from above by special nets which prevent damage from frost - it is an eerie sight right out of a science fiction movie to see acres and acres of green plants cocooned in giant grey nets...

The real objective of my excursion were two places at the very end of the valley: the road to Pascua-Lama, a huge and controversial mining project at the border with Argentina and the Private Natural Reserve Los Huascoaltinos. These two names became lately intrinsically related: Los Huascoaltinos, which literally means "those of upper reaches of Huasco Valley," refer to an agricultural community whose members are descendents of Diaguitas and who are adamantly opposed to the Pascua-Lama project which pretends to extract gold, silver, and copper from a mine and by the way to contaminate a large part of the water coming down from crystal-clear glaciers and snow fields at 5000 meters. The mining project involves the destruction of several smaller glaciers and the use of the water for extraction process which obviously will leave it loaded with chemicals and minerals. And this water is the life-line for the agricultural communities below...

So almost every stone, every traffic sign, every visible wall is painted with slogans like "No to Pascua-Lama," "Pascua-Lama is death for the valley," and the most common one, which can be seen even on the walls of a local day-care center, "Agua vale más que el oro," water is more important (or costs more) than gold.

Some mining companies are notorious for stepping over the Chilean laws and rights of Chilean citizens, and Barrick, the company in charge of the project, is no exception to that rule. According to the Indian traditions, all the valleys are of public use and the access through them may not be blocked. And that particular valey might have been used some 500 years ago by the Incas...

The most outrages part is that Barrick does not own major parts of the valley, so that their sign "Propiedad privada" (Private Property) is not valid and completely distorts the real legal situation. It is a shame and a pity that many Chileans submit themselves that easily to the rule of the stronger bully and tolerate Medieval-style checkpoints mounted by foreign companies which are absolutely illegal and are willing to give up their innate right to access important parts of their territories.

It also came as no surprise to me that when I was driving back from the closed gate and greeted an old Diaguita woman, that she looked back at me with scorn and not responded, supposing that I worked for the company which was going to destroy her valley... Little did she know that we were in the same boat, victims of a mining giant... I could not access the most interesting parts of the valley in my vehicle, she could not stick to her traditional lifestyle.

By the way, if we started talking about the traditional Indian lifestyle, there are several interesting observations to be made. I was very surprised at the level of communitarian organization. The local people here are extremely poor, but their fields are well kept, there is no rubbish lying around; in general, I would say they compare very favorably with other localities.

The best of all, the goats, which are the primary destructors of plant life in northern Chile due to overgrazing, are kept at bay. Despite being one of the major sources of income for the Diaguitas here, the number of animals is kept at reasonable level, and although one can definitively see some damage in the lower parts of valleys, it does not seem to threaten the continuity of the plant life, as is often the case in other parts of Chile.

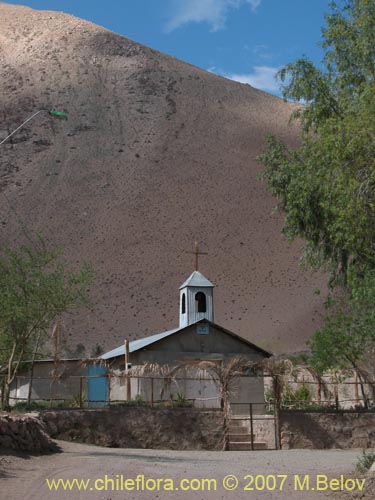

Here and there one can see the results of Catholic work - there are mini-churches in almost every hamlet, but this penchant for western spiritualism seems to be rather superficial, a thin veneer on top of a thousand-years-old way of life.

Well, but the main reason I came to that place was to see the plants... In fact I was able to visit an altitudinal cross-section from 1600 to 2800 m. The main brunt of that area consists of low and sparse bush. Naturally, its composition varies with altitude. In the lower reaches one would find Chuquiraga ulicina, Senna urmenetae, Gymnophyton robustum, a very aromatic shrub, Lycium minutifolium, and Geoffroea decorticans, a tree which produces edible fruits, and Buddleja suaveolens. When you gain height, the dominant shrub species become Senecio proteus, Senecio johnstonianus, and Ephedra breana, a plant which also produces edible fruits. They dwindle out at about 2500 - 2700 m., and beyond that the vegetation becomes very sparse: only small plants which cling to the ground and hardly rise above 5 - 10 cm. Exception are the vegas, high altitude bogs, which present very dense vegetation cover and quite a varied setup of plant species.

But I did not make that high in that area because there are no roads beyond 2000 m. (except for the one which Barrick blocked), and doing a hike which would last several days was not in my plans. It was early spring (the first days of November), so the altitudinal blooming range was just between 1800 and 2800 m.; I did some hinking around the gate and also in the Juntas de Valeriano area. At the upper altitudinal limit I found very few blooming plants, and most were just beginning to open their first flowers there. Below 1800 m. one could find here and there last flowers, but it was evident that the spring has passed already there. So hiking up to let us say 3500 m. would not make much sense. However, if you visit that area at a later time (December - January), there is an excellent hiking / horse riding trail which goes to Laguna Grande (3100 m.), an artificial lake which was constructed to regulate the water supply during the summer, and beyond, where you can definitively find very interesting high altitude species. In the village below (Juntas de Valeriano) some Diaguitas offer mules for rent with a guide for about 50 USD / day, and that may be quite a worthwhile investment, because Laguna Grande is at about 30 km. from the beginning of the trail, and there are several passes beyond that lake at about 4000 m. very much worth a visit.

While there are no large trees except for Geoffroea decorticans in the area, the number of smaller species and their beauty is surprising. When you look at the apparently barren slopes you never would expect to find so many different and interesting plants. Just a few examples:

And probably the most beautiful plant of all that area is Cruckshanksia hymenodon. It belongs to the Rubiaceae family, and its distinctive feature is that it has big white petaloide sepals and long narrow corola, the yellow color of which stands out on the background of the white sepals... In Chile there are several more Cruckshanksias, but this one is by far the most ornamental one:

Cruckshanksia hymenodon var. hymenodon

Escallonia angustifolia var. coquimbensis